Written by: Clare Bishop-Sambrook, Lead Technical Specialist, Gender and Social Inclusion, Policy and Technical Advisory Division, IFAD, Rome

Labour-saving devices have been available for decades – so why are women still working 12 hours a week more than men? This topic formed the main theme for a keynote address by Clare Bishop-Sambrook at the InnovationSharefair in Nairobi on International Rural Women’s Day on 15 October. The daily burden of rural living – particularly for women – is a major constraint to small farmers’ ability to increase agricultural productivity, achieve food security, and improve general well-being. The sheer hard labour will continue to drive young people away from agriculture and rural communities.

The daily burden of rural living – particularly for women – is a major constraint to small farmers’ ability to increase agricultural productivity, achieve food security, and improve general well-being. The sheer hard labour will continue to drive young people away from agriculture and rural communities. Ensuring rural women’s access to relevant and affordable technologies is central to the International Year of Family Farming and the African Union’s 2014 push for agricultural productivity and food security. This is coupled with addressing workload distribution at the household level.

This topic also resonates with one of the proposed targets for the Sustainable Development Goals. Under SDG5 on “Attaining gender equality, empower women and girls everywhere” one target states: by 2030 recognize, reduce and redistribute unpaid care and domestic work through shared responsibility by states, private sector, communities, families, men and women, within the family and the provision of appropriate public services.

Women’s need for access to technologies

Rural women desperately need the benefits of labour-saving technologies and practices to reduce their workload. This is essential to enable them to take advantage of opportunities for livelihoods development and improve their quality of life, including attending to their health needs and enjoying leisure time.What is the evidence of women’s onerous workload? Data from a World Bank study[1]found that in Malawi, for example, in the busiest month of the year women worked for a total of 48 hours per week on productive and household duties, in comparison to men’s 36 hours (Figure 1).

Both sexes spent around 23-24 hours per week working in agriculture. Women spent a further 13 hours on cooking, washing, etc, six hours collecting water and another two hours collecting firewood.

Both sexes spent around 23-24 hours per week working in agriculture. Women spent a further 13 hours on cooking, washing, etc, six hours collecting water and another two hours collecting firewood. These domestic tasks barely featured in men’s workload, accounting for just over 2 hours of their workload per week. Instead, men spent nine hours of non-agricultural time in income-generating activities.

Even in the quietest month of the year, women worked 39 hours per week and men only 27 hours. This pattern was repeated among girls (15 hours per week) and boys (11 hours) at the busiest time of the year. The data confirm that women are overburdened by many labour-intensive and repetitive tasks, which earn them no money, and have little seasonal variation.

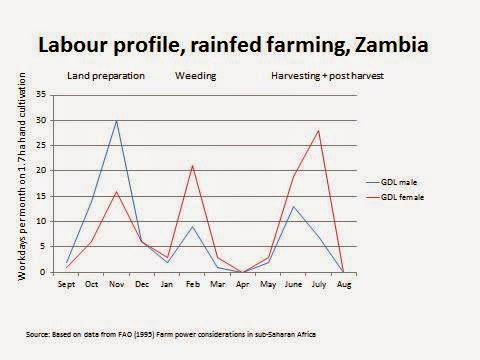

There is also a marked division of labour between women and men within farming activities. For example, in a rainfed farming system in Zambia where the land is cultivated by hoe, men do the bulk of the digging, whereas women are busier with weeding, harvesting and post-harvest activities (Figure 2).

There is also a marked division of labour between women and men within farming activities. For example, in a rainfed farming system in Zambia where the land is cultivated by hoe, men do the bulk of the digging, whereas women are busier with weeding, harvesting and post-harvest activities (Figure 2). The question arises as to whether a typical smallholder farming family has sufficient labour to meet all the peak labour demands in a timely manner. The reality is, that with around 80 per cent of the cultivated land in sub-Saharan Africa prepared using a hand hoe, many smallholder families struggle to keep pace with the seasonal farming calendar. This results in reduced productivity and an inability to adopt improved farm inputs and practices which require additional inputs of farm power.

And the picture is exacerbated if family labour is withdrawn from agriculture – for example, if family members migrate, children attend school full-time or if women have to walk further in the dry season to collect water.What are the opportunities for agricultural growth?

Labour-saving technologies and practices can ease the burden of work by making existing farming systems more efficient. The use of draught animals or tractors (two-wheel or four-wheel) can reduce the labour requirements for land preparation. But when this results in an expansion in the area under cultivation, this effectively shifts the labour burden from the man to the woman because she will now have a much larger area to weed and harvest, largely by hand. New practices can change the labour requirements for crop production. For example, both men and women benefit from minimum tillage and the planting cover crops. Alternatively, services may be hired in – be it labour, draught animals or machines. But even here, women are disadvantaged. Recent work by the World Bank and others[2]found that the returns to hired labour are lower when the labourers are hired by women than when hired by men. Various reasons are cited: women may not be able to afford to pay as much as men for effective farm workers; cultural norms may mean that labourers work harder for a male supervisor; and women may not have enough time to supervise their labourers well.

Gender transformative agenda

Because of the burden of domestic work, we can’t talk about improving agricultural productivity without reducing the domestic workload, especially if women are to realise their productive potential. We need to bring reliable, safe water supplies closer to the home; we need energy-efficient cooking methods (fuel efficient stoves, woodlots and low-cost biogas systems); we need hand-operated or motorised food processing equipment; and we need affordable driers and storage systems to reduce post-harvest losses.

But many will observe, correctly, that these technologies have been available for at least a couple of decades. Efforts have been made to ensure that gender considerations have been mainstreamed into design and delivery: they are relevant to women, communicated to them through appropriate channels, available locally, affordable (with micro-finance, if necessary) and women are trained in their use.

So why we are still talking about the need for low-cost labour-saving technologies and practices for rural women in 21st century?

Because making machines available is like addressing the symptom, but not the cause. We need gender transformative approaches to tackle the underlying causes of gender inequalities. Gender mainstreaming is necessary, but not sufficient. We must address the cultural norms that restrict women’s access to technologies and strengthen women’s voice to influence household expenditure patterns to include technologies that would reduce their domestic workload.

Men need to appreciate the extent of workload imbalance between household members and its adverse impact on household productivity. They need to commit to do something about it, and that includes taking on more responsibility for domestic tasks.

This topic needs more visibility in policy dialogue to promote public infrastructure investments that reduce rural workloads. We need to make greater use of proven methodologies that are available to create a supportive environment for positive behaviour change and equitable workload balance, such as community conversations, community listeners’ clubs and household methodologies.

In conclusion, there are two key messages for improving agricultural productivity on smallholder family farms.

- First, we must address labour constraints across the whole livelihoods system at household level, including those in the domestic sphere, rather than just looking to reduce the agricultural workloads.

- Second, we must break down the gender division of labour and achieve equitable workload balance in farming and household tasks. This means we need to go beyond gender mainstreaming and use gender transformative approaches to achieve sustainable changes at the household level for the benefit of all.